Contact

XNew Novel Pre-release Announcement: “An Uncalculated Risk,” Book 3 of “The Cain Series,” Coming May 2025.

An Uncalculated Risk, book 3 of The Cain Series, will publish this May, 2025, in ebook, paperback, and hardcover formats. Like all Cain Series novels, An Uncalculated Risk is an episodic, near-future, cyberpunk, science fiction novel. In this installment, Cain and Francesca travel to South America to uncover the monstrously wealthy force behind a mercenary invasion of Bolivia, which has disrupted their tin exports and, consequently, Francesca’s seawall project. Nothing is every as it seems, though, and the cat-and-mouse of spycraft soon escalates to armed conflict.

Back-cover copy:

“In the fusion age, war for commerce had become a commonplace. But when an unusually well-financed mercenary force seized the Alto Madidi mining complex in the Bolivian Andes, they set off a cascade of events that brought the global tin market to its knees—and threatened Francesca Pieralisi’s seawall project. Tin was indispensable to the manufacture of construction exoskeletons, called “connies,” and connies were the only means by which the seawall could be built, to reclaim the farmlands that would stave off the looming threat of famine.

To discover who had hired the mercenaries—and to determine if their goal was simply theft or an attack on EU interests—EU INTCEN tasked Francesca (and, with her, Cain) to go to Bolivia and find the truth. What they found was a plot by the richest man on Earth—or off of it—and a global extortion conspiracy involving bribery, kidnapping, and war. Francesca, undaunted by the odds, would stop at nothing to save her seawall project, but soon found herself betrayed by her own zeal, manipulated into compromising her reputation and career, and saw her life pushed to the cliff’s edge.

Cain must now fight through a web of off-world, sovereign corporations, conspiracies and counter-conspiracies, to make a lie the truth, and to pull Francesca back from oblivion. From Sovereign Trade Zones in the American South to the rainforests of South America, Cain battles not only to remove the mercenary brigade, but to short-circuit the machinations of a trillionaire in An Uncalculated Risk, book 3 of The Cain Series.”

Like Ethos of Cain, book 1 of The Cain Series, An Uncalculated Risk is told in five parts, as Cain and Francesca pursue one clue after another, hunting down those responsible for the invasion. I’ll release the cover art next month—and it’s a good one, too—followed by publication of the novel in May.

As a special sneak preview, An Uncalculated Risk will likely NOT be the only Cain Series novel published in 2025. I’m on track to have book 4 in the series ready for publication by the end of the year. Whether that means late November or early December remains to be seen; there are several factors involved, including cover creation, proofreading, typesetting, etc, and any one of them could suffer a delay. I’ll have a better idea by summer’s end and will post another update on book 4 then. For now, I’d like to say thank you to every reader who has enjoyed—and especially to those who took the time to review, always massively appreciated—Ethos of Cain and A Desperate Measure. I hope you will check out An Uncalculated Risk this May.

Stories within Stories: The Episodic Form and Novel Cycles in “The Cain Series.”

Introduction:

With the new year upon us, and with the publication of book 3 of The Cain Series coming at the end of spring, I wanted to take some time to discuss the series’ structure and format and how they might impact readers’ speculations about the series’ direction. Some readers have already reached out with their theories about what will happen next (with most people keying off of the first and last lines of A Desperate Measure), and I wanted to pour a little fuel on that fire.

The Episodic Form: a primer

All books in The Cain Series are and will be episodic, near-future, cyberpunk science-fiction novels. But what does “episodic” really mean and how do episodic novels differ from more traditional books?

At its most basic, an episodic novel is one where the story is told through a series of separate, though related, parts that add up to something more than a collection of shorter stories, when viewed as a whole. There are several different modes common to episodic fiction (as well as novels that don’t fit nicely into any), with most employing either linear—where each part follows the previous one and leads toward the book’s conclusion—and non-linear—which either tells a story out of sequence or explores a particular theme rather than combining to an overall story; either mode might also employ the same characters throughout or not.

A few familiar examples of episodic fiction may be found in the works of Charles Dickens and Alexandre Dumas. Many of the first episodic novels were the result of serialization, where Dicken’s and Dumas’s novels’ parts were first printed in periodicals, coming out over a series of months. In more recent times, Steven King used the same serializing format for his novel, The Green Mile. With serializing, each episode needs to stand more or less on its own, as readers will not have the luxury of moving immediately on to the next part of the story; so, each part needs to engender enough satisfaction for readers to anticipate—and return for—the next part. Serialized novels are typically linear.

Another classic example, which was not serialized (well, part of it was), is James Joyce’s Ulysses. Ulysses is told chronologically, though not strictly speaking in a linear mode. Though we ostensibly follow Poldy and Stephen around Dublin as they meet people and get into trouble, the book’s episodes do not tell an action-plot story (more on that to come), but rather discuss and exemplify the themes of alienation and yearning.

The episodic form is certainly not restricted to novels, of course: television shows are inherently episodic, as are some movie series. The original Star Wars trilogy is an example of an episodic series (and not simply because each movie is given an episode number in its prologue), telling the story of Anakin Skywalker’s redemption. Readers will also find the episodic form used in plays, musicals, operas, comics, graphic novels, and other media.

In The Cain Series, I employ the linear episodic form, where each part of each book follows its predecessor, but I have also further refined the form by applying classic dramatic structure to the parts, both internally and at the novel and series levels. Now what the hell does that mean?

Classic Dramatic Structure

Dramatic structure is a way of arranging the parts of a story—whether episodic or not—to make it more effective, engaging, and sensible. And whether you have received specific training in dramatic structure (e.g. a degree in literature, drama, or film) or not, you are, in fact, an expert in it—because it is used absolutely everywhere. Classic dramatic structure has its roots in ancient Greece, where plays were offerings to the gods, but is more commonly known by Gustav Freytag’s definition of the five-act structure. Freytag called the five acts introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. I don’t know that these definitions speak as effectively to contemporary readers today as they may have in 1863, so I tend to translate them thus: in act 1, we meet the characters and maybe learn a little about the world of the story; in act 2, we learn more about the world and, importantly, the situation or problem that the story will confront; in act 3, the protagonist sets out to do something and usually hits a snag of some sort toward the act’s end (the complication); in act 4, the protagonist overcomes the complication (or not, if the story is tragic) and then, in act 5, we reach the denouement, or the wrap-up of the story.

In addition to the five-act structure, there is its refinement, the three-act structure, which we have all seen in countless movies and TV shows. The three-act is quite similar in structure to the five-act: in act 1, we meet the characters and learn what it is that they want to do; in act 2, they try to do it and hit a complication; in act 3, they overcome the complication (or not) and then wrap things up with the denouement.

Now, this may all seem pretty darn formulaic—and it is—but that does not have to mean boring. Oh, it absolutely can result in a boring story, regardless of medium: I’m sure we’ve all experienced numerous stories where we have anticipated the entire thing in the first few pages or minutes and find ourselves bored nearly to death by the tedious predictability of it all. That anticipation, which undermines us in bad storytelling, however, is the product of our expertise with dramatic structure: if we did not know how it all works, we would not anticipate it so accurately. That same expertise of ours, though, can be called upon by good writers to create tension, suspense, to inspire our imaginations as we wonder what the complication will be or how the heroes will overcome it—or not—or even if the story will have a happy or tragic ending. As with so many things in life, it all comes down to the execution.

In The Cain Series, I employ dramatic structure on three levels, with the first, obviously, appearing at the part level (levels two and three to come, a little further down). Each individual part of each book is discrete, that is standalone; they usually follow a three-act structure, though sometimes a five, and tell a self-contained story. For example, part 1 of Ethos of Cain sees Cain breaking into von Hauer’s villa on Paradise Orbital, to extort him out of stock that Lester needs to take over Arcadia Planitia, on Mars: in part 1 of A Desperate Measure, Cain tracks a stalker through a maze of streets and AI limitations.

Now, as Ethos is told in five parts and Desperate is told in three, both of these parts do not have the luxury of space that a traditionally structured novel would. Though it complicates the writing process (episodic ain’t for the timid), structuring the novels this way also produces a number of advantages, too.

Advantages of the Episodic Form

There are several distinct advantages to employing the episodic form, the first of which is speed. As every critic and reader’s review has stated, The Cain Series novels are fast-paced. This is a result of each part’s size and discrete nature, that is, its requirement to reach a satisfying conclusion within a limited space. In a five-act structured novel like Ethos of Cain, each part is roughly the size of a novelette; for a three-act structured novel like A Desperate Measure, each part is roughly the length of a novella. In both cases, each individual part needs to tell its story quickly—or I’ll run out of space. So, out of necessity, Cain Series novels enjoy a lightning-fast pacing (I say enjoy, but obviously that depends on the reader; if you enjoy fast pacing, you may enjoy The Cain Series; if you do not, you almost certainly won’t).

The next advantage is that each part of each novel is action-packed. Since each part is discrete, it comes with its own complication and resolution, and in a kick’em-in-the-teeth, cyberpunk, action-adventure story, that usually entails someone getting fucked up. And so, in each part, readers will find a corresponding action sequence. Now, writing a series of action-packed episodes does require some finesse and consideration. If every action sequence has the same level of danger, the same scale, and the same stakes, the book will quickly become tedious and predictable. Raymond Chandlier said it best, as is so often the case: “it’s like you’re playing cards with a deck full of aces: you’ve got everything and you’ve got nothing.” If, however, we go back to our classic dramatic structure for a cue, we can employ rising action, that is, increase the stakes, the scale, and the danger as the novel progresses, helping to keep the action fresh and exciting.

The third major advantage to the episodic form is the simplification of complex plots. When you have a complicated plot, such as what appears in A Desperate Measure, with a trillion-euro government project (the seawall), the avarice of a sovereign corporation (BHI), and the corruption of an official (spoilers!) raging out of control, it can often lead to the plot bogging down in the details or the readers becoming impatient with elements that do not seem terribly exciting. By taking such a plot and breaking it down into its component pieces, however, readers are only ever asked to acquire a little bit of knowledge at a time, with the rest of the prose dedicated to plot and characters. Again, for example, part 1 of A Desperate Measure introduces us to the surveillance AI and the seawall project, while focusing on Cain’s cat-and-mouse conflict with the stalker; these elements, though—the project and the surveillance AI—are fundamentally important to understanding parts 2 and 3. And so, even though each part’s plot is discrete, subsequent parts of the book benefit from the knowledge acquired in the previous parts. By the time readers come to the act 3 climax, they already possess the presuppositions necessary to enjoy it—Serval blind spots, exoskeletons, sovereign-orbital money laundering—but without ever having to slog through pages and pages of slowly-paced exposition.

There is also an additional benefit to the episodic form employed in this manner, which is seen at the book-level (the second level), rather than at the part level, and that is the melding or mingling of action- and character-driven plots.

Plots, Plots, Plots:

Though plots come in many forms and styles, they can usually be characterized as either an action-driven plot or a character-driven plot. The basics: an action-driven plot revolves around what the characters do (e.g. Cain fighting his way into a hidden research facility to steal a quantum field generator), while a character-driven plot concerns what the characters think, feel, and who they are, their identities. Most novels, regardless of format or structure, are either one or the other, though—like yin and yang—also usually contain a bit of the other. The bit of the other, though, is usually a subplot, that is, something minor that takes place alongside the main plot. In your typical romance novel, for instance, the character-driven plot is often a “will they or won’t they” plot, resolved by the protagonists getting together in some way (or not), while there is also an action-driven subplot (e.g. a terminally ill spouse, a big project at work, etc) that may act as an instigating moment for the lovers. Subplots, however, never get as much space and are never as important as the main plot; if they were, they’d constitute the main plot. Except, of course, in episodic fiction.

In Cain Series novels, with three to five discrete plots per book, a mix of character-driven and action-driven plots can be found, along with subplots involving either. Take part 3 of Ethos of Cain for an example: the action-driven plot involves Cain performing two rescue missions—Odhiambo’s and Walker’s—with their juxtaposition illuminating Cain’s character (i.e. what he will do versus what he will not); there is also a romantic, character-driven subplot involving Cain’s relationship with Francesca, about how his constantly risking his life is stressing her out, making life intolerable. But, though each of the five parts of the novel employ action-driven main plots, the book’s main plot is character-driven, a “will they or won’t they” plot resolved by Cain and Francesca discovering a way to live their two very different lives together.

And this facet of The Cain Series novels brings us, finally, to stories within stories, because the book’s plot amounts to an additional story, beyond the five stories told by the five parts.

Stories within Stories:

Though each part of a Cain Series novel tells a discrete story, it also performs a double-duty, in that each part also constitutes an act in the novel’s structure. In Ethos of Cain, part 1 tells its own story, yes, but it also fulfills the overall book’s need for an act 1, introducing the main character, Cain, and a few important facets of the world. Part 3 is also a self-contained story, while simultaneously providing the novel with its act-3 complication, which is (spoilers!) Francesca breaking things off with Cain. In part 3’s plot, Francesca’s choice to end things creates a tragic end, but in the novel, her choice creates the complication that the two of them must overcome. By structuring the parts and novel in this way, by writing Cain Series novels with multiple, discrete stories and having them combine to tell an additional fourth or sixth story (the book’s), the same exact words on the page tell multiple stories at the same time.

So, in Ethos of Cain, the parts each tell an action-driven story about Cain’s life as a soldier of fortune in the near future, while—combined—they tell a character-driven story about his identity, his sense of self, and whether he can maintain his idea of who he is, his character and dignity, while somehow changing enough to continue his life with Francesca.

The stories-within-stories told by each novel, however, go further still, in that the individual novels also play an additional role, similar to how their component parts do, by contributing to yet another, even larger story (the third level). I call these multi-novel stories “novel cycles.”

Just as each part of each Cain Series novel contributes an act to the novel’s structure and story, each Cain Series novel does the same, contributing an act to the novel cycle’s structure and story. A novel cycle, therefore, works much the same way as the novels that compose it: three or five novels taken together will tell an additional, larger story.

Now, with book 3 not due out until late spring, 2025, we have yet to see a complete cycle—but it’s on its way.

I’m sure many readers will be able to deduce the first cycle’s story once book 3 comes out (actually, a few have already done so, just on the basis of books 1 and 2), but as a little nudge to the imagination, I will say that the first cycle of The Cain Series novels is composted of the first five books; thus, each of the first five novels tells both its own story and contributes an act to the first novel cycle (i.e. book 1 is act 1 for the cycle, book 2 is act 2 for the cycle, etc). Knowing what we now know (or already knew) about classic dramatic structure, readers may very well anticipate the stories that books 4 and 5 will tell, once they have finished reading book 3 and recognize the novel cycle’s complication. We shall see.

Beyond the first novel cycle, the plan at the moment is for books 6, 7, and 8 to comprise cycle 2, followed by books 9 through 13 comprising cycle 3. That isn’t set in stone, not just yet, but as I have already outlined those cycles, it will likely play out that way. More to come on those cycles once we’ve completed the first.

Conclusion

“But, Seth, my dude, do I really have to know all this stuff about structure and episodes and all that jazz, just to enjoy these books?”

You don’t, no. This is just a little insight into how the series functions. Like any other literary technique—foreshadowing, literary allusion, extended metaphor, personification—the point isn’t to wow audiences with the author’s staggering genius (well, that’s not my goal, anyway), but to tell a great story. Just as a driver doesn’t need to know how the car’s engine is made or works, how many times the ABS pumps the breaks when decelerating, nor the revolution ratios for the differential—not just to drive the car and enjoy its acceleration, safety, and handling—the same is true for a good book: you don’t have to know that a conflict is coming up soon because of the structure; if done well, you’ll feel it anyway, in the characters’ voices, in the too-quiet of an alleyway, because nothing is that easy. If you are into literary technique, though, just like a car guy is into cars, then, by all means, have a poke around under the hood of The Cain Series. These novels are built to last.

In a future update, I will discuss the role of technology and technological revolution in the series theme—and then, a little later on, a new theme that will begin, probably with book 9. Until then, I hope you will find new and deepened enjoyment in The Cain Series and will check out book 3, this spring.

Happy reading!

What is cyberpunk?

Since the beginning of The Cain Series, a question that I often receive is, what is cyberpunk? The short answer is that cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction, which developed throughout the 1970s and officially began in July of 1980 with the seminal publication of John Shirley’s novel City Come A-Walkin’. William Gibson—the author of Neuromancer, cyberpunk’s most renown work—famously said of John Shirley, “he is cyberpunk’s patient zero.”

Though definitions of the subgenre abound, many—sadly, most—unfortunately focus upon the aesthetic so often found in the first, golden-age cyberpunk novels of the 1980s: rainy cityscapes with neon signs—in Japanese—punk-rock clothes and handheld computers, and maybe a tough cookie in an alleyway lighting a cigarette with a cybernetic arm. The style, however, was simply a facet of the time in which the first cyberpunk novels were written, combined with their tendency to be set in the near future. There are many other, non-cyberpunk books that employ the same style, even books that are not science fiction.

So then, what is cyberpunk and how does it differ from traditional science fiction?

Cyberpunk differs from traditional science fiction in its core conceit, the central idea around which the worlds and plots and characters are built.

In traditional science fiction, going all the way back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—which was not only the first novel, but the first horror novel and the first science fiction novel—all the way through Verne and Wells, to Asimov and Herbert and, yes, to Phillip K. Dick, traditional science fiction’s core conceit is that all technological progress, regardless of any ill purposes to which antagonists might put it in the short term, is of net benefit to humanity. To say it more simply, in traditional science fiction, all technological innovation is good, even if the bad guys use it for their own selfish needs for a while: Death Stars don’t kill people, Darth Vader does.

This all-innovation-is-good-for-humanity approach is, in fact, the central idea behind Asimov’s extraordinary Foundation Series, which has gone on to inspire generation after generation of science fiction writers. From Herbert and Dick to Roddenberry and Lucas, even if technological innovation is used by bad peopled for bad purposes, the good guys will eventually recapture the innovation and use it for good.

Cyberpunk takes a different, more nuanced approach to the subject of innovation: cyberpunk’s core conceit is that all innovation—technological, social, governmental, criminal—regardless of its intended or actual benefits to humanity, will, ultimately, be exploited by the powerful to take advantage of everyone else.

The classic example of cyberpunk’s core conceit is found in the ubiquitous cyborg. The benefit to humanity of cybernetic replacement of damaged or missing limbs and organs is obvious: imagine the benefit—the joy—that such technology would bring to someone injured in a car accident or a war, to have their ability to walk returned to them. Now imagine what advantages an unscrupulous mega-corporation or criminal syndicate or fascist government could take if they used the same technology to replace the limbs and organs of their operatives, creating cyborgs so fast, strong, and heavily armored that no mere human could resist them—and then imagine a battalion of such soldiers air-dropped onto a rival’s corporate headquarters or national capitol. That’s cyberpunk.

And so, in cyberpunk—not the rainy, neon, Japanese alleyway stuff, but real cyberpunk—the novels explore the many potential innovations that the powerful might exploit. From the super-powerful AIs of Neuromancer, to the genetically engineered NuMen of Streetlethal, to the personality coding of Mindplayers, cyberpunk explores the wonders of tomorrow—and brings with them a warning.

Some readers may see a similarity between cyberpunk and Luddism: they are not, in fact, similar. Luddites reject technological innovation, where cyberpunk accepts the benefits, while acknowledging the dangers. It is one of the reasons that cyberpunk protagonists are so often masters of some tech or other: it’s how they acquired the power to challenge the antagonists.

More can be said about the obligations of the subgenre, of the frequently recurring tropes and themes, and certainly any science fiction might warn us of the dangers inherent in a burgeoning technology (which happens often, only in trad sci-fi, the blame is placed on bad humans). But the core conceit of cyberpunk—that all innovation, regardless of its benefits, will be used by the powerful to exploit the rest of us—guides the writers who explore cyberpunk’s possibilities.

Ever since an irate librarian denied my request to order a copy of Neuromancer (I was a ten-year-old with an attitude, admittedly, but I think she was under the impression that cyberpunk novels were somehow manuals for computer crime), I have been fascinated by the possibilities inherent to cyberpunk, a subgenre of science fiction that delves deeply into not only innovation, but into the human condition. Cyberpunk fascinates me as much today, all these decades later, as it ever did, and exploring the innovations of the next century, through the novels of The Cain Series, is every bit as artistically satisfying and thought-provoking as reading those forbidden novels of the 1980s. It has been a long road and a hard one, to develop the skills and experience to create the cyberpunk novels that I had always aspired to write. And it was worth every step.

Seth W. James

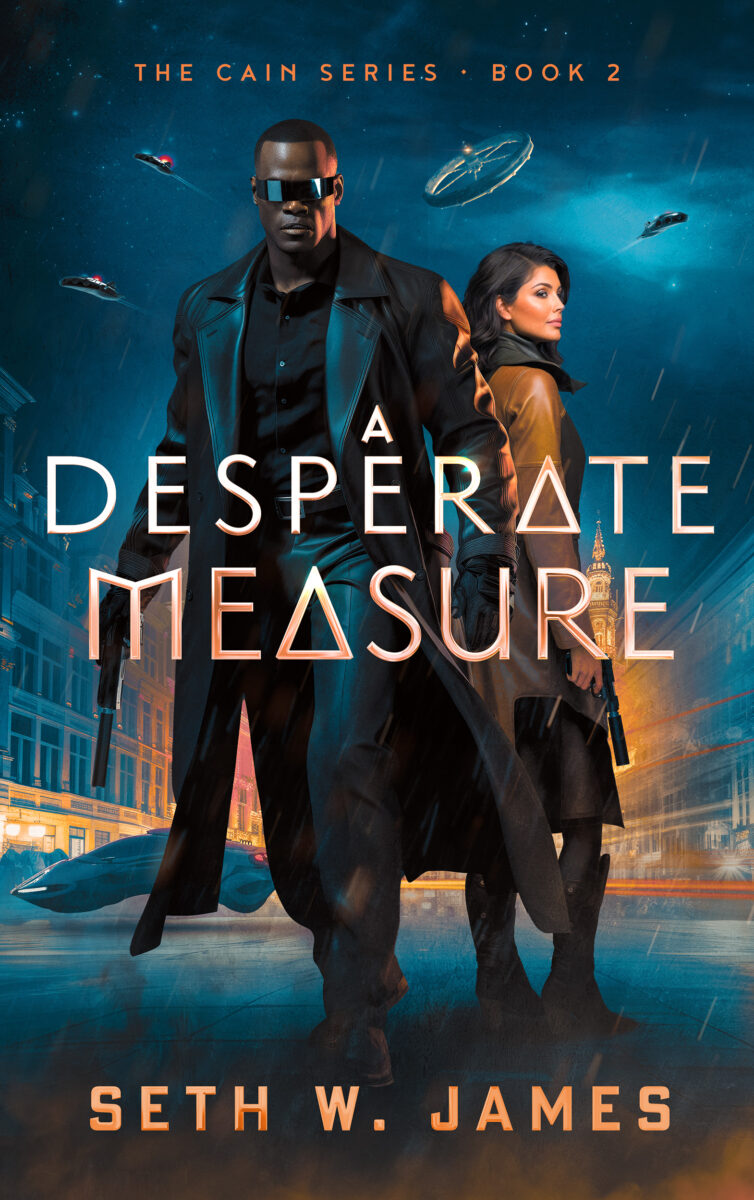

Cover Art Pre-Release for “A Desperate Measure,” Book 2 of “The Cain Series,” Launch Date June, 2024

Here is a first look at the cover art for my new novel, A Desperate Measure, book 2 of The Cain Series, which comes out this June, 2024.

Another terrific cover from the artists at Damonza. Not only does Cain look even better than he did on the cover of Ethos of Cain, but they did a great job introducing Francesca, appearing for the first time. Francesca will likely grace some of the covers of The Cain Series, though not for every book; Cain’s adventures may require solo action, occasionally, and the covers will reflect that distinction. All in all, though, I am very pleased with the new cover art and can’t wait to see it in print.

New Novel Pre-release Announcement: “A Desperate Measure,” Book 2 of “The Cain Series,” Coming June 2024

I am pleased to announce that A Desperate Measure, book 2 in The Cain Series, will be published this June, 2024, in ebook, trade paperback, and hardcover formats. A Desperate Measure, like its predecessor Ethos of Cain, is an episodic, near-future, cyberpunk, science fiction novel, which continues the story of Cain and Francesca, as they struggle against corporate, governmental, and criminal forces, each intent upon plundering the seawall project that Francesca had risked so much to launch.

Cover copy:

“In A Desperate Measure, book 2 of The Cain Series, several months have passed since Cain and Francesca took down the fascist cabal of billionaire Dietrich Stinnes. Riding the wave of celebrity that her victory had inspired, Francesca stepped down as the Mayor of Venice to join the newly-formed European Seawall Foundation, to shepherd the project she had fought so hard to create, with Cain at her side as her Chief of Security. What should have been a blissfully dull—though vitally important—assignment soon became as dangerous as any period in their lives, when off-world corporation Black Horizons, Inc. infiltrated the ESF, intent upon diverting a portion of the foundation’s staggering budget to their bottom line—by any means necessary.

Cain must soon return to his roots in corporate crime, to counteract BHI’s attempts to neutralize Francesca. From circumventing the surveillance-state AI, to battling mercenaries on the streets of Brussels, to hunting corrupt cops through a deserter colony on the Latvian coast, Cain struggles to intercept each new—and increasingly aggressive—threat. BHI, however, have nothing to lose through violent escalation: they are a sovereign corporation, their orbiting headquarters placing them not only above Earth, but above its laws, as well.

Faced with the crippling effect that BHI’s extortion would have on the seawall project—and with the hundreds of millions who would suffer famine without the new farmlands it would create— Francesca must decide if times have grown desperate enough for a desperate measure.”

Where Ethos of Cain was told in five parts, A Desperate Measure is told in three, with the multilayered, character-and-plot-driven story exploring the consequences of sovereign orbitals, the surveillance state, AI, and the depths of corruption. Book 3 in The Cain Series, which is already underway, will return to the five-part format and explore the evolving characters of Cain and Francesca, as the series races toward a pivotal complication.

I want to send out a big thank you to all the readers who have enjoyed Ethos of Cain and hope that you will equally enjoy A Desperate Measure. I plan to release the cover art next month, followed by the novel’s publication in June.

Until then, happy reading!

“Ethos of Cain” featured on SFWA’s Insta

Ethos of Cain, book 1 of The Cain Series, was recently featured on the official Instagram of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writer’s Association (formerly known as the Science Fiction Writers of America). Here’s a link to their “First Lines Friday” post: https://www.instagram.com/p/C3bJe5LSSFD/. There was a second post, as well, featuring the cover art from Ethos of Cain along with three phrases describing it, “Three Phrase Thursday,” they call it, but those posts are a part of an “Instagram Story” and apparently are not available in perpetuity. Oh well (the three phrases were, “Raw fusion-powered cyberpunk,” “With gritty infiltrator action,” and “And one hell of a romance, too;” there was a character limit of some sort, which made for an interesting writing challenge).

If you have Instagram and are looking for your next favorite book, the SFWA’s account may be the perfect addition to your feed. They post content throughout the week from the authors of sci-fi, fantasy, cosmic horror, and related genres, everything from “Mascot Monday,” where you can meet the pets of your favorite authors, to “Writing Desk Wednesday,” for a peek at where the magic happens, to “Three Phrase Thursday,” and “First Lines Friday.” And if you find a book you like, the posts are usually linked back to the author’s accounts, if you want to add them to your feed, too.

I’ve never been much for social media, not since I was a boy sneaking computer time at a friend’s house or the school library, to delve into the forbidden wonders of BBS culture. Following a youth filled with “Anarchy Philes” and homemade flamethrowers, detailed instructions on how to run a phone-card scams (which went over my head), and recipes for things like thermite (which never worked), today’s social media seems (thankfully) tame by comparison. It’s probably for the best, though I imagine you can still find those thermite recipes if you really wanted to. As for the celebrity gossip and state actors hurling propaganda, well, I think I’d rather spend my time writing my next novel.

Speaking of which . . .

Sex and Violence

Anyone who has read my novels will have found plenty of sex and violence, from protagonists dodging CIA assassins on the streets of Cairo, to love requited for a married woman and the man she couldn’t have, to battling orcs or exploring undercover kink or walking balls-out into a room full of fascists to save a lover or die trying, I have written a hell of a lot of sex and violence. A fundamental question to writing such scenes, however, is: what makes an action or love scene good? Or, conversely, what takes a violent set piece or sexual episode and drags it into tedium? Surprisingly, the exact same things.

Despite sex and violence largely representing two opposites—that is, creation and destruction (with exceptions, of course; martial arts, for instance, are violent yet creative)—effectively writing either requires the same approach, challenging writers to avoid the same pitfalls. It is all too easy, when launching into an action sequence or walking a pair (or more) of protagonists back to the bedroom, to focus on the mechanics of the situation, to become lost or bogged down in depicting rather than storytelling. The solution, fortunately, is the same for these sorts of scenes as it is for all others: focus on the reader. When I approach such scenes, I ask myself, how will it move the plot forward and what knowledge—about the characters, their arcs, their capabilities, vulnerabilities, etc.—will the reader gain from the telling? If the scene I envision doesn’t move the plot or tell us something new about the characters, deepening the readers’ insights, then I either change it or cut it.

So, what does that look like on the page? Let’s start with sex. Imagine a hardboiled detective from the 1940s and his acid-blonde torcher client returning to his office after a night of trying to get the skinny on a movie producer who stole her inheritance. Classic. They hadn’t found much at the clubs they had visited, except for one clue. They talk it over, decide what to do, and then the dick makes a pass at the blonde and, for once, she doesn’t slap his face. The clothes come off, a long scene depicting genitals in action commences, and, when it ends, the blonde lights up a coffin nail, throws on her clothes, says, “thanks for the drink, mac; I’m going for a massage; pick me up at eight,” and the dick wonders where he’s going to find a clean shirt.

Does this sex scene succeed? No, it doesn’t; no matter how erotic or inventive the genitals-in-action catalogue, we, as readers, know nothing more about the characters than we did beforehand and the plot hasn’t moved: the detective and client still only have the one clue, their feelings for one another haven’t changed, and we haven’t learned anything about their personalities, where they’re going or why. So, what would make the scene effective? Change it so that the detective wants to drop the case, that he doesn’t think the clue is worth it and that he’s worried about the three other cases he supposed to solve; then, have the blonde seduce the detective, to keep him interested and working the case. Why does this scene work where the sex-for-fun scene largely does not? It works because now we know more about the characters and the plot: we lose confidence in the clue and, as readers, start looking at other investigative avenues; we also know more about the detective, that he’s worried about his other cases, that he’s willing to drop a client if the case has little potential, and that he’s a bit of a sucker; we also learn that the blonde is willing to do anything, isn’t too romantic in her opinions about sex, and that maybe she’s hiding something, if she still thinks there’s a case when the facts don’t support it. In short, the second version works because it is a part of the story and the first one doesn’t work because it is extraneous. Now, could the second version be written with a catalogue of genitals-in-action? Sure. Would it hurt it? Well, that’s largely a matter of taste, both the writer’s and readers’. If the blow-by-blow account (pun intended) doesn’t illustrate the character’s state of mind or intentions, etc., then the readers may wonder why it is there. Pandering rarely succeeds.

Action scenes also need the same focus on characters and plot and can fail when they focus too much on mechanical sequences and gore. Consider: our detective has uncovered the blonde’s true motive behind the investigation, to locate her polygamist husband and rub him out; unfortunately for the detective, the husband, and his second wife, the blonde has tailed him to the husband’s new home and is armed with tommy gun. The blonde opens up on the house, blowing out the front windows; the husband and wife drop to the floor and are showered with glass; the dick barely gets off a couple rounds from his revolver, hitting nothing. The blonde kicks in the front door and lets off a long burst to her left, nearly decapitating the dick, who dives behind a steamer trunk that he hopes has something more solid in it than linens. The blonde then swings back to the other direction, roars in fury, and shoots the husband, catching him in the shoulder; he stumbles back, crashing into the China cabinet, and then the blonde opens up full-auto, riddling his torso with fifty rounds of hot lead, punching through his lungs, exploding blood out of his mouth in his last desperate breath. As the husband’s bloody corpse slips to the floor with a sound like a butcher slapping hamburger into wax paper, with his new wife screaming until her throat bleeds, the blonde turns her fury and her sub-machinegun on the other woman. The dick sees that it’s now or never, pops up over the steamer trunk, and puts a round from his revolver straight through the back of the blonde’s head, shattering her skull and spewing grey matter over the remains of the China.

Does this scene work, even as a finale? It does not. Clichés to one side, it fails because of its focus on blood and guts and the mechanics of the scene, rather than on the people enacting it. With the exception of the word “fury,” we have no real insight into the blonde’s motivations, what she feels—if anything—in that long-awaited moment of revenge. All we get, instead, is the sequence of her assault on the house, which might be okay if there were obstacles to overcome rather than elongating “she entered the house,” followed by a description of the husband’s death that receives as many words as the rest of the scene. Could it be salvaged? Sure. If the focus of the scene is instead changed to the people enacting it, rather than just the events, it could work, particularly if it is the finale. If the blonde has to employ tactics and patience, pinning down the detective until he runs out of ammunition, it would show that her fury runs cold, is calculated, and may satisfy the readers’ predictions about the blonde, developed from earlier scenes. If the husband tries to shield his new wife or push her out of the room, it deepens his character beyond being a cad who couldn’t be bothered to divorce one (admittedly intense) wife before marrying another; we’d care just a little bit more about him. If, after fighting her way into the house, the cold and calculated blonde begins to shed tears as she kills the husband, it would reveal something other than the baser instincts of ownership or propriety, signaling that even the femme fatale has a beating heart somewhere inside. Again, what makes a sex or violence scene work is its contribution to the plot or to our understanding of the characters.

Are there exceptions? You bet. Sometimes a sex scene or a scene of violence is a species of celebration. If the plot of the book (or show or movie or whatever) is or involves a “will they or won’t they” arc, where we, the readers, wonder if those two crazy kids will ever get it together, then the sex scene where they finally do get together celebrates, in a way, their plot’s success. It can be taken too far, of course, but a little salaciousness in that moment constitutes the payoff for the readers’ emotional investment in the characters. Again, focusing on the character’s joy in such a scene, their experience, will save it from seeming awkward. If the reader comes away feeling as though they just witnessed the writer masturbating in public, yeah, you’ve failed. Keep it in your pants, fella. And, of course, the same can be true for action scenes: the final defeat of the BBEG calls for a little explicit description, a payoff for the readers who, hopefully, have come to dislike Mr. Big Bad. And, of course, like the celebratory sex scene, it can be taken too far: if the specificity of the kill or the duration of its description gets out of hand, the reader may feel that they are reading the writer’s confession about a hated, personal opponent, rather than the protagonist’s. As T.S. Eliot wrote in Tradition and the Individual Talent, “The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality,” by which Eliot meant that we, as writers, should keep our prejudices out of our works and, instead, focus on giving the work what it needs to succeed. You, as a human being, may have really hated your kindergarten teacher, but the detective isn’t shooting her for you: he’s shooting the blonde to protect wife number two—and the scene will be better if it stays that way.

To sum up: scenes of both sex and violence succeed when they move the plot forward and show us something about the characters. That is, after all, why we write them in the first place.

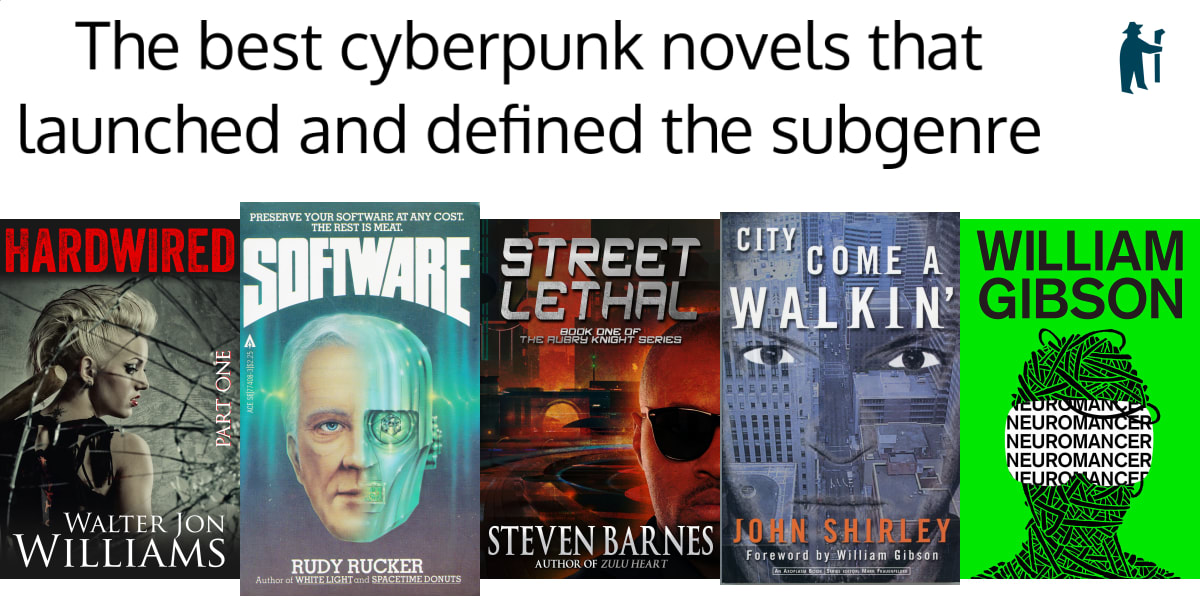

My Top Five Cyberpunk Novels List Now Appears on Shepherd.com

To coincide with the launch of Ethos of Cain, I collaborated with the folks at Shepherd.com to create a new recommendation list: The best cyberpunk novels that launched and defined the subgenre. If you haven’t been to their site yet, Shepherd is a book recommendation source—with a twist. Rather than aggregating users’ lists, Shepherd collects recommendations from authors: each list includes one recent work by the author and then five works that the author loved or that inspired their work or contributed to a genre, a moment in history, or other interest.

You can find my Shepherd list here: https://shepherd.com/best-books/cyberpunk-that-launched-and-defined-the-subgenre

I chose to focus on the golden-age cyberpunk novels, starting with City Come A-Walkin’ by John Shirley—cyberpunk’s “patient zero,” as William Gibson calls him—and continuing through the subgenre’s first years of existence. These are great books, not only enjoyable and thought-provoking to read, but important to the history of cyberpunk and science fiction, generally.

Shepherd has other cyberpunk-related lists, too, which you can find here: https://shepherd.com/bookshelf/cyberpunk. And, of course, lists on any other genre or subject you might want to explore, by authors you know or may discover for the first time.

I hope you enjoy The best cyberpunk novels that launched and defined the subgenre list and Ethos of Cain.

Happy reading!

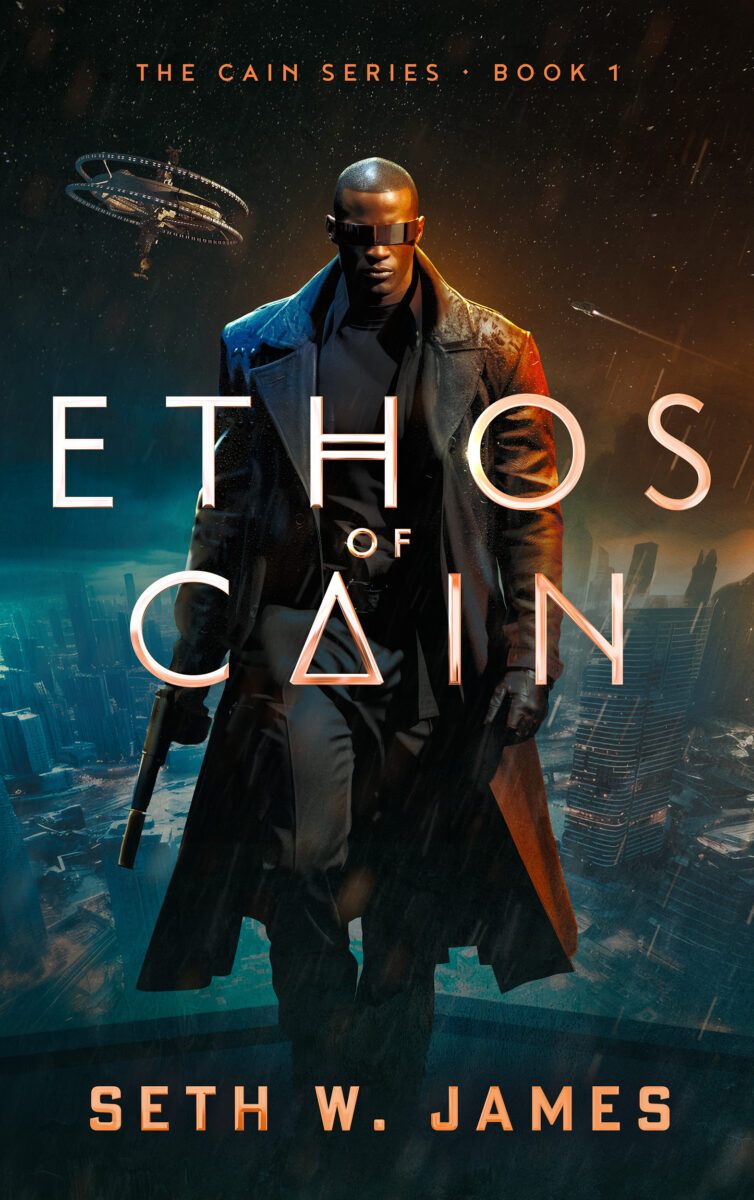

New Novel Release, “Ethos of Cain” by Seth W. James, Book 1 of The Cain Series

Ethos of Cain, the first novel in The Cain Series, debuts today exclusively on Amazon, in ebook, trade paperback, and hardcover formats. An episodic, near-future, cyberpunk science-fiction novel, Ethos of Cain explores a world in the grip of technological upheaval, the nature of identity and change, and the ever-widening grey area between criminal, corporate, and governmental power.

Cover art and back-cover copy:

“The perfection of cold fusion and CasiDrive propulsion had lifted humanity into the wider solar system—and widened the gulf between the nameless masses and the sovereign-class wealthy. Into the grey between corporate and criminal walked Cain, a soldat de fortune, who, for the last twenty years, had taken scores and completed contracts for the elites of any world, impenetrable, abstruse, and solitary.

All of that changed one year ago when, after a triste with a former client turned into a romance, Cain’s relationship with Francesca caused him to question how he could walk in her world and survive in his own. The boundaries of their lives then came crashing to Earth when the man whose syndicate they had destroyed returned for revenge. The money behind the man, however, concealed a deeper, more sinister plot, one that threatened Francesca’s life and would challenge Cain to walk the razor’s edge between their two worlds while remaining true to the Ethos of Cain.

Ethos of Cain is the first novel in The Cain Series by Seth W. James.”

The Cain Series will follow Cain and Francesca as they delve into the deepest underworlds and soar to the farthest flung colonies to challenge the powers of the next century, to wrest from them a future worth living. Set in the near future, where the perfection of cold fusion and CasiDrive propulsion have lifted humanity into the wider solar system, the series explores the collision of boom-industry expansion, the worsening effects of climate change, and the warring-states corporate power structure created by sovereign orbitals.

It has been a great pleasure writing the first novel in The Cain Series and designing the next several books to come. Book 2 is already underway and I hope to have it ready for publication by next summer or early fall, 2024.

Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoy Ethos of Cain!

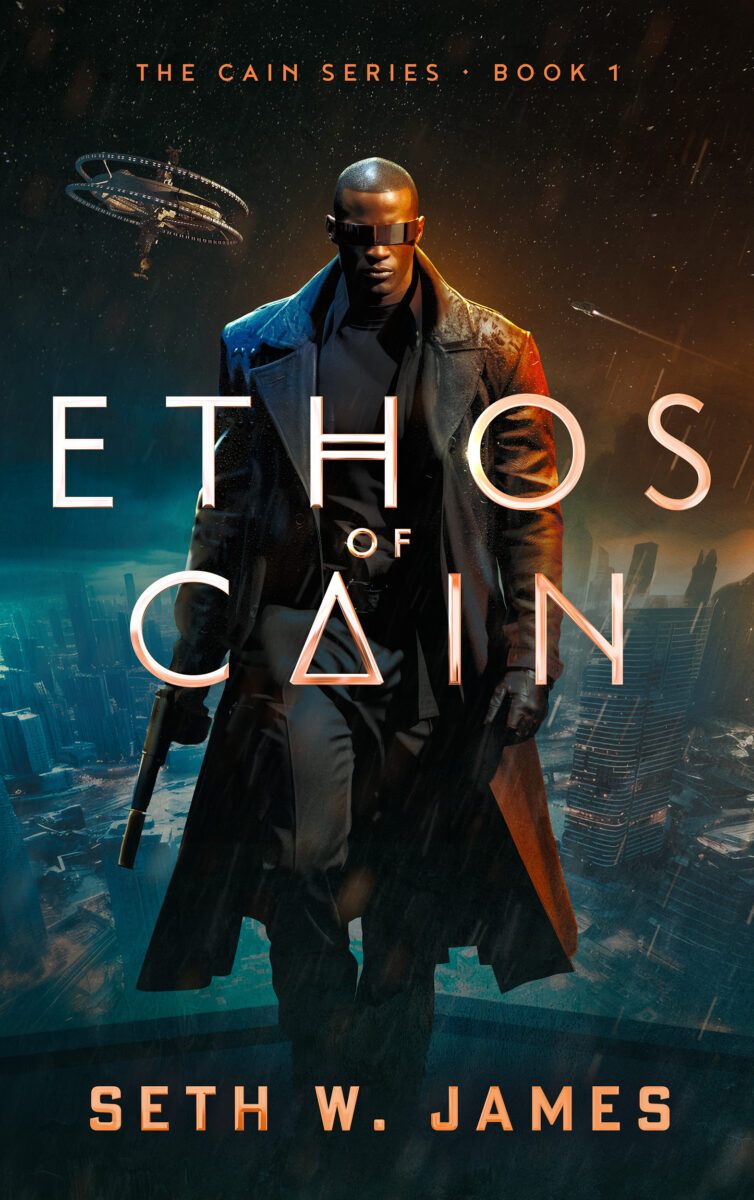

Cover Art Pre-Release for “Ethos of Cain,” Book Launch September, 2023

Here is a sneak peek at the cover art for my new novel, Ethos of Cain, which comes out this September, 2023.

The artists at Damonza delivered again with a great cover. I had a rough idea of how the cover should look, with a ton of small details that could link to the text, and Damonza just took those elements and ran with them. They actually returned four awesome covers for the first round, each a masterpiece in its own right, before working with me to refine the image into what you see above. I couldn’t be happier with it, either. In my mind’s eye, this is what I saw while writing Cain. The orbital looks fantastic, too.

Anyway, hope you enjoy the cover art. Only a month to go before the release of Ethos of Cain. See you then.